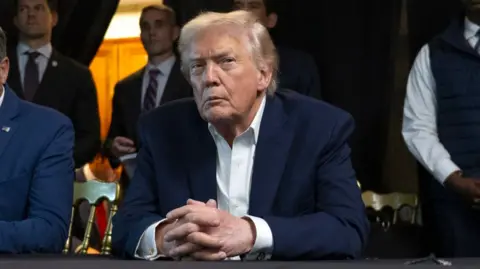

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio will meet Danish and Greenlandic officials next week to discuss the fate of Greenland - a semi-autonomous territory of Denmark that President Donald Trump says he needs for national security. The vast island finds itself in the eye of a geopolitical storm with Trump's name on it and people here are clearly unnerved.

Yet when you fly in, it looks so peaceful. Ice and snow-capped mountains stretch as far as the eye can see, interrupted here and there by glittering fjords - all between the Arctic and the Atlantic Oceans. It is said to sit on top of the world; much of it above the Arctic Circle.

Greenland is nine times the size of the UK but it only has 57,000 inhabitants, most of them indigenous Inuit. You find the biggest cluster of Greenlanders on the south-western coast in the capital, Nuuk. Parents dragged their children home from school on sledges, and students mooched their way in and out of brightly-lit malls. Few wanted to talk to us about the Trump-related angst here. Those who did sounded very gloomy.

One pensioner banged his walking stick on the ground in emphasis as he told me the US must never plant its flag in Greenland's capital. A lady who said she was mistrustful of everyone these days admitted she was 'scared to death' about the prospect of Trump taking the island by force after she watched his military intervention in Venezuela.

Meanwhile, 20-something pottery-maker Pilu Chemnitz said: 'I think we are all very tired of the US president. We have always lived a quiet and peaceful life here. Of course, the colonisation by Denmark caused a lot of trauma for many people but we just want to be left alone.'

Never mind opposing a takeover by the US, which 85% of Greenlanders say they do, most also say they favour independence from Denmark - although many tell me they appreciate the Danish subsidies that help prop up their welfare state. While rich in untapped natural resources, poverty is a real issue here in Inuit communities.

Overall, Greenlanders want a bigger, louder say, not only in their domestic policies, but in foreign affairs too. I went to the island's modest-looking parliament, the body of it built in a Scandinavian style with wooden slats and painted the same burnished red as the Greenlandic flags fluttering by the entrance.

I asked Lynge-Rasmussen if she felt that big global powers - the US, Denmark, Nato, and the EU - were talking a lot about Greenland right now, rather than to the islanders about their fate. She nodded vigorously. Surprisingly, perhaps, she blames Denmark more than she blames Trump for overlooking Greenlanders' wants and needs. But Lynge-Rasmussen insisted that Greenlanders should not see themselves as victims in the current situation. Instead, she suggested they use the international spotlight now on them to show off their importance and push for their priorities.

Greenland's geopolitical importance is underscored by factors such as the shortest route for a Russian ballistic missile to the US via Greenland and the North Pole, making it a point of strategic interest that prompts US actions. With a delicate balance in Arctic relations threatened by escalating tensions, Greenlanders seek a peaceful resolution as global focus turns to their icy shores.

Yet when you fly in, it looks so peaceful. Ice and snow-capped mountains stretch as far as the eye can see, interrupted here and there by glittering fjords - all between the Arctic and the Atlantic Oceans. It is said to sit on top of the world; much of it above the Arctic Circle.

Greenland is nine times the size of the UK but it only has 57,000 inhabitants, most of them indigenous Inuit. You find the biggest cluster of Greenlanders on the south-western coast in the capital, Nuuk. Parents dragged their children home from school on sledges, and students mooched their way in and out of brightly-lit malls. Few wanted to talk to us about the Trump-related angst here. Those who did sounded very gloomy.

One pensioner banged his walking stick on the ground in emphasis as he told me the US must never plant its flag in Greenland's capital. A lady who said she was mistrustful of everyone these days admitted she was 'scared to death' about the prospect of Trump taking the island by force after she watched his military intervention in Venezuela.

Meanwhile, 20-something pottery-maker Pilu Chemnitz said: 'I think we are all very tired of the US president. We have always lived a quiet and peaceful life here. Of course, the colonisation by Denmark caused a lot of trauma for many people but we just want to be left alone.'

Never mind opposing a takeover by the US, which 85% of Greenlanders say they do, most also say they favour independence from Denmark - although many tell me they appreciate the Danish subsidies that help prop up their welfare state. While rich in untapped natural resources, poverty is a real issue here in Inuit communities.

Overall, Greenlanders want a bigger, louder say, not only in their domestic policies, but in foreign affairs too. I went to the island's modest-looking parliament, the body of it built in a Scandinavian style with wooden slats and painted the same burnished red as the Greenlandic flags fluttering by the entrance.

I asked Lynge-Rasmussen if she felt that big global powers - the US, Denmark, Nato, and the EU - were talking a lot about Greenland right now, rather than to the islanders about their fate. She nodded vigorously. Surprisingly, perhaps, she blames Denmark more than she blames Trump for overlooking Greenlanders' wants and needs. But Lynge-Rasmussen insisted that Greenlanders should not see themselves as victims in the current situation. Instead, she suggested they use the international spotlight now on them to show off their importance and push for their priorities.

Greenland's geopolitical importance is underscored by factors such as the shortest route for a Russian ballistic missile to the US via Greenland and the North Pole, making it a point of strategic interest that prompts US actions. With a delicate balance in Arctic relations threatened by escalating tensions, Greenlanders seek a peaceful resolution as global focus turns to their icy shores.